Police chases killed 3 bystanders in Chicago last year – It’s time to rethink policies

6:50 PM CDT on March 22, 2021

Guadalupe Francisco-Martinez, 37, was fatally struck in her car last June by an officer involved in a high-speed chase.

In 2017, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that police vehicle chases kill an average of 355 people every year. That figure is troubling enough, but trends in traffic policing in Chicago indicate the problem could be getting worse.

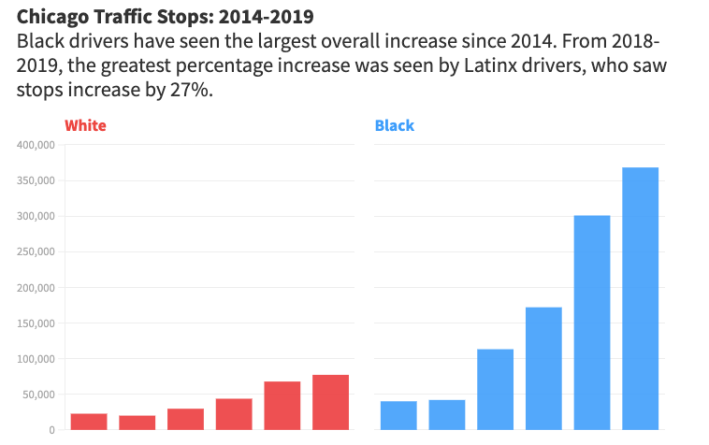

According to data from the Illinois Department of Transportation, Chicago traffic stops increased dramatically from 2014 to 2019, rising from about 87,000 to over 598,000 – a 587-percent increase in just five years. It’s also important to note these stops disproportionately target Black and Latinx drivers; Both groups are stopped 5.6 times more frequently than white drivers, but are no more likely to be in possession of contraband. The ACLU has inferred that traffic stops have taken the place of stop and frisk, with traffic infractions providing a pretext for the police to conduct searches.

During a 2018 Chicago Tonight discussion of the Chicago Police Department's practice of writing exponentially more tickets for minor bike violation in Black communities than majority-white ones, Chicago Police Department director of public engagement Glen Brooks was upfront about the fact that the department enforces traffic laws more stringently in high-crime neighborhoods as a strategy to intercept illegal guns.

"When we have communities experiencing levels of violence, we do increase traffic enforcement,” Brooks said. However, he maintained that, "It isn’t a matter of fact that we are targeting people of color. We are trying to do everything humanly possible to curtail the violence." But the reality is, when the police focus traffic enforcement in high-crime neighborhoods, which in Chicago means Black and Latinx communities, most of the drivers police try to stop are going to be Black and Latinx.

While national data on the number of people killed annually from police vehicle chases hasn’t been updated since the 2017 report, it’s safe to assume that a steep increase of traffic stops would result in an increase of drivers fleeing stops, and consequently a rise in the number of crashes resulting in the injury or death of the person fleeing, their passengers, police officers, and/or innocent bystanders.

Since the beginning of Illinois' pandemic Stay at Home order a year ago, there have been at least a dozen cases of police chases ending in crashes, often with major property damage and injuries, and sometimes resulting in deaths. Here are some recent local police pursuit fatality cases.

- On September 2, 2020, a driver fleeing a traffic stop in Gresham crashed into another car, killing Da’Karia Spicer, 10, and critically injuring her brother Dhaamir, 5.

- On September 18, 2020, a driver was killed after fleeing a traffic stop on Interstate 57 in south-suburban Matteson, and crashing into another vehicle in southwest-suburban Chicago Ridge.

- On November 5, 2020, a motorist fleeing officers after running a stop sign near the UIC police station fatally struck graduate student Tushar Sharma, 27, and injured another person.

A particularly high-profile case of a police chase ending in a death last year was the June 5 killing of Guadalupe Francisco-Martinez, a 37-year-old mother of six, whose car was struck near the intersection of Irving Park Road and Ashland Avenue by a police officer involved in a two-hour high-speed, multi-officer chase after a murder suspect that began on the Far South Side. In the wake of that tragedy, the CPD updated its pursuit policy last August.

The force had previously changed its pursuit protocols after another case where a chase led to the senseless death of a bystander. In January 2003, then-sergeant Paul Bauer was pursuing a man who had stolen a wallet in River North when the man stopped at a red and placed the wallet on the road. Bauer disregarded an order to end the chase, and the fleeing suspect eventually collided with another driver in the West Loop, then struck Qing Chang, 25, as she stood on the sidewalk, killing her and her unborn child. Chang's husband was awarded a $17.5 million settlement from the city. (Bauer was eventually promoted to commander, and was fatally shot outside the Thompson Center while confronting an armed man in February 2018.)

In the wake of Chang's death, the 2003 policy revision prohibited pursuit for minor offenses like theft, including theft of a vehicle. According to the policy, CPD officers are charged with applying an in-the-moment “balancing test” to determine if “the necessity to immediately apprehend the fleeing suspect outweighs the level of inherent danger created by a motor vehicle pursuit.”

The 2020 policy revision added a few more restrictions and procedures regarding pursuits, plus new incident reporting requirements. It also states that “The department will not discipline any member for terminating a motor vehicle pursuit.”

But these policies can hardly be considered progressive. The latest revisions in the CPD pursuit policy now align with a set of recommendations issued by The U.S. Department of Justice and National Institute of Justice in 1990, more than 30 years ago. The conclusion of the "NIJ Restrictive Policies for High-Speed Police Pursuits" states that “High-speed vehicle pursuits are possibly the most dangerous of all ordinary police activities,” and recommends finding alternatives to pursuit whenever possible. Under a section entitled “Pursuit Alternatives” the NIJ policy unpacks just how rarely a vehicle chase should pass the CPD balancing test:

When offenders are known, they can probably be apprehended, without chases, in their homes or in places they frequent. Whether or not to engage in a high-speed chase then becomes a question of weighing the danger to the public of the chase itself against the danger to the public of the offender remaining at large. For anyone other than a violent felon, the balance weighs against the high-speed chase. It is important, then, that a law enforcement agency equip itself with means of identifying a suspect without high-speed pursuit. The most obvious solution is to take a photo of the fleeing vehicle, which entails having a camera available and an officer capable of taking a useful photo with it.

This sensible policy recommendation from 1990 begs the question: in the 21st Century, an age of traffic cameras, satellite images, and police body cams, are police chases necessary? In what circumstances does any immediate danger the suspect presents to the public outweigh the potential for endangering officers, suspects, and innocent bystanders?

Certainly the threat posed to the public by the drivers who initially evaded traffic stops in the Da'Karia Spicer and Tushar Sharma cases didn't, in the CPD's words, "outweigh the level of inherent danger" created by the vehicle chases that resulted in the tragic deaths of a little girl and a young grad student. The CPD pursuit policy and “balancing test” needs to be rethought.

Thanks to Stephan Foley for bringing this issue to our attention.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

They can drive 25: At committee meeting residents, panelist support lowering Chicago’s default speed limit

While there's no ordinance yet, the next steps are to draft one, take a committee vote and, if it passes, put it before the full City Council.

One agency to rule them all: Advocates are cautiously optimistic about proposed bill to combine the 4 Chicago area transit bureaus

The Active Transportation Alliance, Commuters Take Action, and Equiticity weigh in on the proposed legislation.