Commuter trains rumble by every few minutes while four Metra workers tell me inside a control tower how they keep 370 trains moving every day. The machine that controls switches between tracks has been operating since 1937. There needs to be more reliable and resilient equipment in place, but it's not a cheap or easy job to replace an ancient system.

Next to the Western Avenue Metra station, at Hubbard and Rockwell, is the A2 interlocking, a massive group of switches – Metra's busiest – that allow trains to cross multiple tracks. There are eight tracks here, and 20 switches.

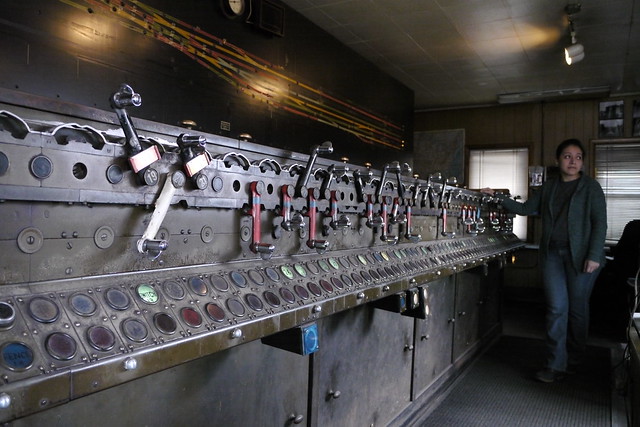

Inside the tower there's a machine larger than a station wagon that's operated with hand-thrown levers that move the track switches outside via compressed air. There are two employees, one to coordinate train movements, and another who sets the levers. On the day I visited, Dave and Sylvia were working. Their work never stops, and no one comes to relieve them for a full lunch. But there are plenty of lulls after the morning rush hour.

A planning document from summer 2015 year said that the commuter rail agency was going to spend $2 million to engineer grade separation. Metra spokesman Michael Gillis said that plan had changed since then, and at the same time offered me a tour of the facility.

The machine is well-maintained by a couple of mechanics, who can make their own replacement parts in a shop below the tower. But the institutional knowledge of fixing the machine is held by only one or two people at a time.

The 370 trains that the A2 interlocking carries are a mix of Metra, freight, and Amtrak trains. Half of the trains are moved between 6:15 a.m. and 2:15 p.m. If the machine breaks, there's no alternative way to set the switches, and a major intersection would grind to a halt. Only electric switches elsewhere in the track network can be changed – "hand thrown" – on the ground by workers.

Planning a replacement will take a while and a lot of money. Metra is going to replace 10 individual switches this year, after completing four last year, but there's no simple replacement for the machine because you can't swap in a newer model.

The switches are a hindrance to more Metra service. Rich Oppenheim, Metra's senior train master, who joined our little tour, said there's "really no room for additional trains" because of the limitations of the machine and the layout of tracks and switches. "In my mind," Oppenheim said, "grade separation is the only solution, but that would cost huge bucks."

The reason there are so many switches is, well, based on several cascading decisions by multiple railroad companies made over the past century. Remember that Metra wasn't a brand name until 1985, and its parent organization, the Regional Transportation Authority, took over independently operated commuter rail lines in the mid-1970s.

The Union Pacific-West line is a straight east-west route between Elburn and Chicago, and terminates at Ogilvie Transportation Center (view a map). The Milwaukee District-West, Milwaukee District-North, and North Central Service lines all go northwest and cross over the UP-W line to reach Union Station. Additionally, Union Pacific sends all of their trains for maintenance on the other side of the switches.

In the past, according to a map above the switching machine that identifies each switch and track segment, there were additional tracks.

Grade separation would cost hundreds of millions. The Englewood Flyover, which carries two tracks over the Dan Ryan Expressway and other train tracks, cost about $141 million. An A2 upgrade isn't part of the CREATE program that bundles dozens of freight and transit railroad improvements of which the Englewood Flyover was part.

Studying is always the first step and the Metra board needs to approve a five-year civil engineering services contract with a company that will "identify and analyze all the options for improving the A2 interlocker, one of which would be a grade separation," Gillis said.