How can we better link the Far Southeast Side’s disconnected network of public parks?

Chicago's Southeast Side possesses a natural wealth of lakefront and wetlands, but people on bikes can't yet safely access it.

7:52 PM CDT on September 11, 2023

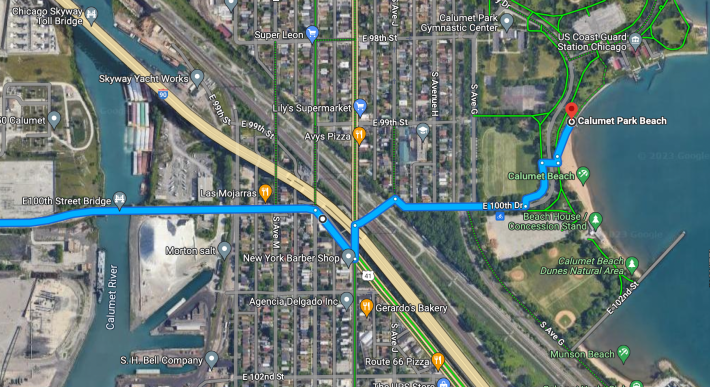

Calumet Park Beach. Photo: Rob Reid

By Rob Reid

Countless drivers crisscross the rugged prairie of Chicago’s Southeast Side, weaving around decaying steel mills, abandoned grain silos, landfills, and recycling plants. Traversing the Chicago Skyway, the Bishop Ford Freeway, or major thoroughfares like 130th Street and Torrence Avenue, motorists might not notice the lakefront beaches or wetland parks fashioned from former industrial sites reclaimed by the city in recent decades. They also might not notice the small number of people on foot and bikes trying to find respite in these natural settings.

From the point of view of the pedestrians and bike riders, it’s hard not to notice the obstacles posed by the area’s car-centric design. Risky traffic crossings and informal paths along medians and grassy verges interrupt a steadily expanding but still insufficient patchwork of bikeways. The bike facilities, mostly just non-protected bike lanes, with no physical barrier protection from traffic, are limited. For instance, the Hegewisch Neighborhood Plan noted that residents felt unsafe on 134th Street near Avenue O due to "excessive speeding by [car drivers]" and the drivers of large trucks, which are supposed to be legally prohibited from this road.

As noted in the Hegewisch plan, the area’s parks remain underused in part because of this limited bike and pedestrian access. As restoration of the area’s parks is a work in progress, so too are interdependent efforts to improve sustainable transportation connecting local residents to the parks.

Three Islands in an Asphalt Sea

Developed from land acquired by the city in 1904, Calumet Park originally served the area’s influx of immigrants working in the steel mills and railyards. The park occupies the Lake Michigan shoreline roughly between 95th and 103rd streets.

Located few hundred yards from the Indiana border, Calumet Park is also only a few miles south of Chicago’s 18.5-mile Lakefront Trail, whose southern terminus is at 71st Street, next to South Shore Park.

There are other lakefront green spaces between the LFT and Calumet Park, including as Rainbow Beach, Park 566, and Steelworkers Park. But creating a seamless route between them remains a complex long-term vision. However the Chicago Park District’s acquisition of U.S. Steel’s South Works facility establishes the land right-of-way to eventually connect all these public spaces.

Unfortunately, Calumet Park is also difficult for Southeast Side residents to access from the southwest. "It’s a death trap," Cook County transit manager Benet Haller said of 100th Street, the most direct route to Calumet Park when approaching from the southwest, during a bike infrstructure tour in August. (Read Streetsblog's writeup of that event here.) Riding east on 100th from Ewing Avenue requires passing under the Chicago Skyway and two freight rail viaducts.

The Burnham Greenway, a useful trail entering the city of Chicago from the south, ends at 100th. The greenway, which follows part of a former railroad corridor to Lansing Illinois, connects Calumet Park to Wolf Lake State Recreation Area, a popular fishing destination straddling the Illinois/Indiana border in the Hegewisch neighborhood.

But the Burnham Greenway, eventually intended to extend 11 miles to State Street in south-suburban Burnham, Illinois, has a 2.5 mile gap, forcing bike riders to share narrow Wolf Lake Boulevard with motor vehicle traffic alongside Wolf Lake and to the south. The Burnham Plan Centennial and the nonprofit organization Openlands say closing this gap would be an effective project in bringing together the region’s unconnected green infrastructure.

In addition to land acquisition, the most significant barrier to bridging Burnham Greenway’s gap is literally a bridge over train tracks near Burnham and Brainard avenues, a project complicated by ongoing negotiations with railroad companies.

Closing the Burnham Greenway gap would also help connect bike riders to the car-free bridge across Torrence Avenue, just north of Brainard Avenue, connecting to a bike-ped path along Brainard and 130th. This route leads to Hegewisch Marsh Park, aka "Little Marsh."

Hegewisch Mark Park is a 129-acre green space that provides a home to cottonwoods and cottontails amidst marsh, wetland, and meadows on the site of former steel mills. The park was the recent recipient of a $500,000 grant from the National Coastal Resilience Fund. As the Hegewisch Neighborhood Plan notes, it’s an "underutilized" resource, in part because it’s hard to get there, located southwest of the intersection of heavily trafficked 130th and Torrence, east of the Calumet River.

East Meets West, Dangerously

Aside from north-south bike trail gaps on the lakefront and the Burnham Greenway, riding east-west is even more problematic for South Side cyclists. Jane Healy commutes more than ten miles on two wheels from her home in southwest-suburban Blue Island to her job at St. Francis de Sales High School, near the northern terminus of the Burnham Greenway. She confronts this challenge regularly.

“People want to go out into nature, take their strollers or bring their grandpa out," Healy said. "And it’s hard.” She noted that drivers have struck her on bike twice, resulting in over $100,000 in surgery and other medical bills.

For her, biking on 130th is out of the question due to a lack of sidewalks and bike infrastructure west of the Calumet river. That leaves 103rd as the next potential east-west crossing. However, "103rd freaks me out and that’s the only way I can go east-west," she said.

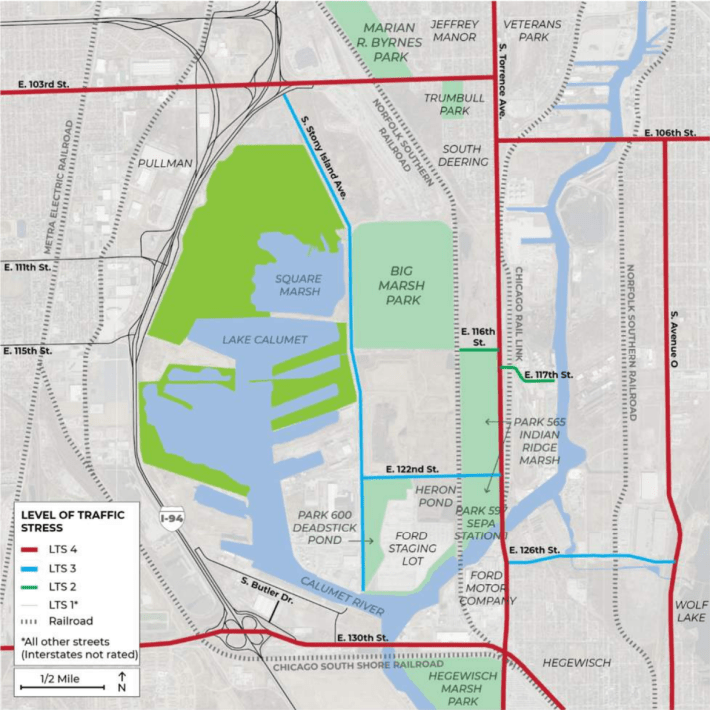

The East Side Neighborhood Connectivity Plan, recently published by Friends of Big Marsh, classified both 103rd and 130th as having extremely high levels of traffic stress.

Respondents to a recent survey by the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, which oversees regional planning, and the Illinois International Port District identified east-west access as the most needed investment for the Lake Calumet industrial site. That ranked above access to nature and exercise.

Visions of Connection

Multiple local stakeholders share overlapping visions of improving transit in the area. In April, Cook County released a Bike Plan envisioning a network of low-stress bike routes reaching within a mile of 96 percent of Cook County residents. CMAP’s own long-range walking and biking plan proposed a “network of continuous greenway and trail corridors, linked across jurisdictions, providing scenic beauty, natural habitat, and recreational and transportation opportunities.”

To build awareness of the limitations and potential for biking on the Southeast Side, the Chicago and Cook County transportation departments organized the ride I mentioned earlier, the Lake Calumet Bike Network Study tour, last month. It led from Hegewisch Marsh Park to Calumet Park. As part of the study, a second tour planned for September 23 aims to highlight sustainable transportation challenges in the nearby Roseland neighborhood.

In 2015, the Active Transportation Alliance highlighted a constellation of potential biking and walking improvements along streets including 103rd and 130th, as part of its Big Marsh Access Action Plan for facilitating access to and across one of the city’s newest parks. The plan also featured a proposed bridge across Lake Calumet at 111th Street.

Building on this and other plans, the East Side Neighborhood Connectivity Plan delves into a concrete feasibility strategy and provides specific recommendations for how to make that work. As Streetsblog noted in July, that plan is a key step in building political will necessary to secure funding for bike and pedestrian improvements.

While the funding requirements are significant, improved access in the region would help area residents and visitors tap into an arguably greater wealth: the area’s abundant park space.

The author also developed an interactive map-based version of this story, linked and below.

Did you appreciate this post? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

One agency to rule them all: Advocates are cautiously optimistic about proposed bill to combine the 4 Chicago area transit bureaus

The Active Transportation Alliance, Commuters Take Action, and Equiticity weigh in on the proposed legislation.

State legislators pushing to merge CTA, Pace, and Metra into one agency spoke at Transit Town Hall

State Sen. Ram Villivalam, (D-8th) and state Rep. Eva-Dina Delgado (D-3rd), as well as Graciela Guzmán, a Democratic senate nominee, addressed the crowd of transit advocates.