No, concerns about equity didn’t kill the Ashland BRT plan. A car-centric backlash did.

2:53 PM CST on December 7, 2021

CTA rendering of bus rapid transit on Ashland Avenue.

35th Ward alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa is generally a friend of the movement for a safer, more equitable, and more efficient Chicago transportation system. Heck, he even gave a speech at the last Streetsblog Chicago online fundraising victory party, which I greatly appreciated. Watch his presentation about sustainable transportation initiatives in his Northwest Side ward below at 10:20 (and keep watching the video for performances by singer-songwriters Meisha Herron and Jill Sobule.)

But I'd like to fact-check some comments that Ramirez-Rosa recently made on Twitter about the city of Chicago's doomed proposal for bus rapid transit on Ashland Avenue.

In the early 2010s, the CTA and the Chicago Department of Transportation did extensive planning and outreach in preparation for creating a major north-south BRT route. The project would have converted two of the four mixed-traffic lanes on a five-lane arterial to center-running, car-free bus lanes with stations in the median, spaced every half-mile. Along with time-saving features like prepaid, level boarding and transit-friendly stoplights, this strategy was projected to nearly double bus speeds, to a near-'L' train pace, with only a minor impact on speeds for private vehicle drivers.

The city initially considered implementing BRT on Ashland between 95th Street and Irving Park Road, or else Western Avenue from 79th Street to Berwyn Avenue. After additional study and public input, Ashland was chosen for the BRT route. However, a couple years after it was announced, the project was indefinitely shelved.

Since then, not much has has happened with BRT in Chicago, unless you count the roughly mile-long downtown Loop Link project, which debuted in December 2015. That initiative, which included converting mixed-traffic lanes to bus lanes, "island" stations, and protected bike lanes represented a nice Complete Streets makeover for the involved corridors but it has resulted in only minor increases in transit speeds, largely because it lacked prepaid boarding and camera enforcement of the bus lanes. Meanwhile, peer cities like New York, LA, and San Francisco have installed dozens of miles of high-speed bus routes.

On Twitter, Ramirez-Rosa blamed our city's failure to make progress on bus rapid transit on the dead-on-the-vine Ashland project, which he said "gave BRT a bad name in Chicago." That's more-or-less accurate. However, he also implied that the reason the initiative was ultimately rejected was because it was inequitable.

Western Avenue should have always been Chicago's BRT poster boy. Give the people on the 49 Western a faster commute and Chicagoans will welcome BRT as manna from above.

— Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa ✶ (@CDRosa) December 3, 2021

But when you take a closer look, his argument that Ashland was a significantly less equitable choice than Western because "much of North Ashland Avenue is just a ten-minute walk from a train," whereas the North Western corridor is a train desert, doesn't really hold water.

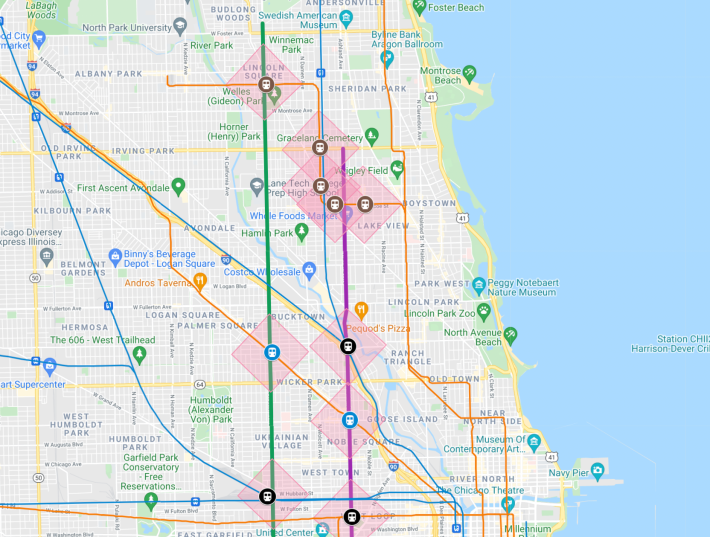

In the map below (view an interactive version here) the proposed Ashland route on the North Side is shown as a purple line, while the Western route is green. The ten-minute (half-mile) "walk sheds" around the relevant CTA and Metra stations – about the longest distance many people are willing to walk to catch a train – are depicted as pink diamonds.

You can see that, contrary to what the alderman implied, only about a mile more of the North Ashland route is located within ten minutes of an existing station compared to North Western. So it's not like building BRT on Western rather than Ashland would have made a major difference in terms of not making "transit-rich neighborhoods on the North Side even richer."

It's also worth noting that a higher proportion of the Ashland route would have have existed on the South Side than the Western route, since the former would have terminated at 95th while the latter would have ended two miles further north at 79th.

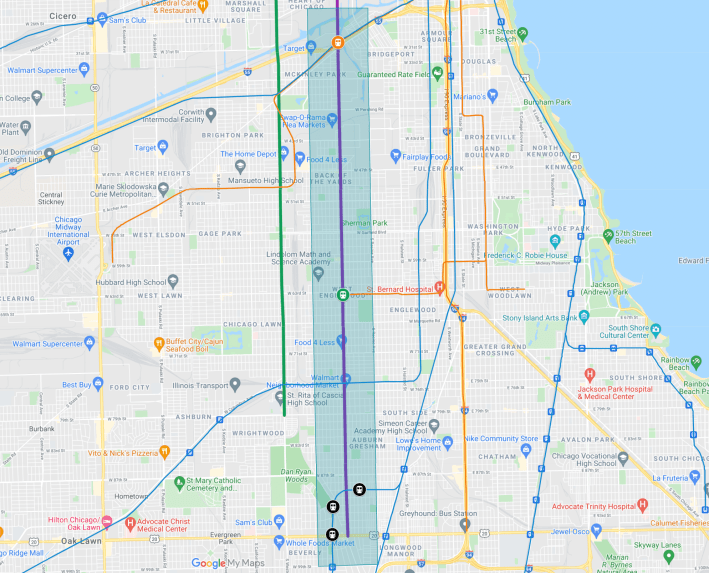

And, like BRT on Western, a rapid bus route on Ashland would have have been a huge win for transit equity, because it would have provided train-like service to long swaths of the South Side that aren't within a convenient walk of an 'L' or Metra station. You can see that on the map below, where the ten-minute walk shed from South Ashland is shown as a light-blue band. (View an interactive version here.)

That's not to say that BRT on Western wouldn't have also been a great option. But Ramirez-Rosa's argument implying that the Ashland proposal was indefinitely back-burnered and "gave BRT a bad name in Chicago" because it was inequitable is off-base.

Rather, the real reason the Ashland BRT project went nowhere had nothing to do with social justice. It was because drivers, who are less likely to be low-income or working-class than transit riders, freaked out at the prospect of mixed-traffic lanes being converted to bus-only lanes, and plans to prohibit some left turns off of Ashland. That's despite the fact that officials predicted little impact on car speeds, and Chicago's relentless grid offers many routing alternatives.

A misleading Not In My Back Yard-style campaign against the Ashland BRT plan, which then-mayor Rahm Emanuel ultimately caved to, was led by Fulton Market Association executive director Roger Romanelli. He's currently lobbying for spending billions in federal infrastructure funds to rebuild the Lake Street 'L' to make it easier to drive under, which gives you an idea of just how much equity concerns were a motivation for killing BRT on Ashland. That is, not at all.

The exact same kind of NIMBY backlash would have surely happened if the city had chosen Western for BRT instead. So it's not that city officials need to pick a more equitable route for bus rapid transit next time. They just need to show some backbone.

In addition to editing Streetsblog Chicago, John writes about transportation and other topics for additional local publications. A Chicagoan since 1989, he enjoys exploring the city on foot, bike, bus, and 'L' train.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

One agency to rule them all: Advocates are cautiously optimistic about proposed bill to combine the 4 Chicago area transit bureaus

The Active Transportation Alliance, Commuters Take Action, and Equiticity weigh in on the proposed legislation.

State legislators pushing for merging CTA, Pace, and Metra into one agency spoke at Transit Town Hall

State Sen. Ram Villivalam, (D-8th) and state Rep. Eva-Dina Delgado (D-3rd), as well as Graciela Guzmán, a Democratic senate nominee, addressed the crowd of transit advocates.