Chicago’s Bike Plan Is Inequitable, Says Report Based on Wrong Map

6:11 PM CDT on September 3, 2015

There’s great potential to use statistics and mapping technology to help ensure that bicycle resources are distributed equitably to people of all races and income levels. For example, Streetsblog’s Steven Vance and data scientist Eric Sherman recently recently worked with Slow Roll Chicago cofounder Oboi Reed and analyzed Census data to get a sense of how well Chicago's existing bike network serves African-Americans, Latinos, and non-Hispanic whites.

They found that whites currently have significantly better access to off-street paths and conventional bike lanes, the only type of bikeways that existed in Chicago before Rahm Emanuel became mayor in 2011. However, it appears that access to bikeways has improved for people of color since 2011, and a higher percentage of African Americans than whites currently live near buffered or protected lanes.

“Equity of Access to Bicycle Infrastructure,” a new report by Rachel Prelog,a Colorado-based urban planning grad student, commissioned by the League of American Bicyclists, establishes a method for using geographic data to help decide whether a bike network is equitable. The report, which uses Chicago as its case study, has some valuable aspects.

However Prelog used a faulty map of the city’s planned bike network, and didn’t fact-check her work with Chicago Department of Transportation. As a result, the report makes unsubstantiated claims that the new network would provide subpar access for the African-American and Latino communities that are most in need of better transportation options.

First, the good parts of the study. “Bicycle equity stems from an understanding that unbalanced conditions exist that require a deeper look,” Prelog writes in the intro. “It may be that some groups are better able mobilize resources to leverage their positions, realizing their needs and wants.”

That has certainly been the case in Chicago, where the lion's share of bike facilities have historically gone to dense, relatively affluent, largely white, North Side neighborhoods with high existing levels of biking. However, that dynamic is changing, thanks to groups like Slow Roll and Bronzeville Bikes, who have been pushing for better bike infrastructure on the South and West Sides.

Prelog sets out to use data to identify “who is benefiting from current bicycle networks and who is disadvantaged” through the creation of a "Bicycle Equity Index." This is a measurement of the relative need for safe biking infrastructure within subsets of Census tracts, based on the age, race, and income of residents, rates of car ownership, and access to transit and retail.

Using accurate data from the city of Chicago’s geographic information system portal, Prelog first analyzes Chicago’s bikeway network as it existed in 2013, the latest year for which Census data is available. She found that 56 percent of Chicago’s Latino population and 57 percent of the African-American population lived over a quarter-mile from a bike lane or path, compared to 50 percent of the city's total population. It's useful to know that access was inequitable two years ago, although those numbers may have changed somewhat since then, due to new bikeways like the Bloomingdale Trail.

However, the report runs into trouble when Prelog makes statements about what the effect on equity would be if Chicago built its planned bike network. She found that the new network would provide 23 percent more of the African-American population with quarter-mile access, but a disproportionate number of African Americans would still live outside of the network.

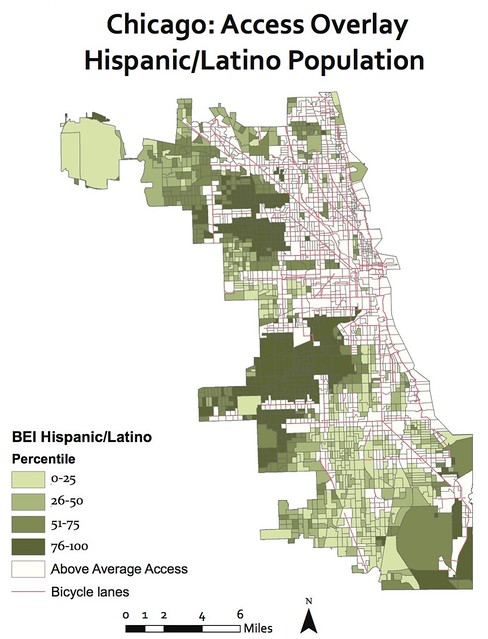

Moreover, the report states, only one percent more of the Latino population would get access to bikeways, despite having the largest rate of bike commuting of any local ethnic group. “Implementation of the full build bicycle network would do little to improve access for Chicago’s Hispanic/Latino community,” she asserts.

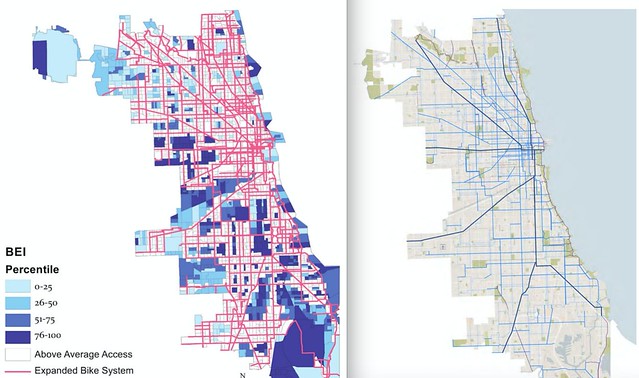

However, I noticed that Prelog’s “planned network” map didn’t jibe with the one in CDOT's Streets for Cycling Plan 2020. When I emailed Prelog to ask where she got her data, she reiterated that she culled it from Chicago’s data portal, adding that she spoke with someone at the city's Innovation and Technology Department who manages the GIS data to clarify how bike routes are classified.

Upon closer inspection of the report's "planned network" map, I realized that it contains many obsolete “recommended routes,” from previous editions of CDOT's Chicago Bike Map. For the 2015 edition, all of the routes that don't actually have lanes, sharrows, or wayfinding signs have been deleted. Moreover, many of the old recommended routes don't appear in the 2020 Plan.

CDOT Spokesman Mike Claffey confirmed that Prelog’s “planned network” map is wrong, and that no one contacted the department to check her work. "We’ve just been made aware of the report and will review it,” he stated. “But it does not appear to reflect the tremendous progress we’ve made in expanding the city’s bicycling network in recent years, nor does it reflect the proposed routes as identified in the Streets for Cycling Plan 2020."

After I figured out what the problem was, I notified Prelog. “It may be true that [the city’s] data has not been updated to reflect changes to how they want to classify their proposed lanes,” she responded. “This is often a reality of data, though, as coordination and work loads between departments are not seamless.”

It appears that Prelog did get bad GIS data from the Innovation and Technology Department, so the city should update that information. However, the reason why her maps are inaccurate is less important that the fact that they are wrong.

"This case study should not be viewed as an indictment of Chicago’s current or planned network," the report states. However, due the use of bad data, the document portrays the city's planned bike network as unfair to African American and Latino residents, when that may not be the case.

Prelog's work could potentially do a lot of good for the cause of bike equity, and I look forward to seeing her analysis applied to the bike network Chicago is actually planning to build. If it turns out that the planned network is, in fact, inequitable, it will be important for CDOT to address that issue.

However, before we can get a sense of whether the 2020 Plan is fair or not, the League of American Bicyclists needs to retract the report and have Prelog overhaul it. The LAB did not provide a comment by press time, but we’ll provide an update if we hear from them.

In addition to editing Streetsblog Chicago, John writes about transportation and other topics for additional local publications. A Chicagoan since 1989, he enjoys exploring the city on foot, bike, bus, and 'L' train.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

The de-facto ban on riverwalk biking is back. What should we do about it?

In the short term, new signage is needed to designate legal areas for cycling on the path. In the long term CDOT should build the proposed Wacker Drive protected bike lane.

Today’s Headlines for Thursday, April 25

It’s electric! New Divvy stations will be able to charge docked e-bikes, scooters when they’re connected to the power grid

The new stations are supposed to be easier to use and more environmentally friendly than old-school stations.